Dreams are illusive. As quickly as the lucid state of consciousness comes upon us and delves our minds into fantastic reality, we awake with images and glimmers of events that possessed our minds in a mysterious period of time. We remember what we can and maybe even hide those dreams that shake our senses. There are countless deciphers of dreams; psychologists, mediums, doctors, coworkers and friends. We search for the meaning of our dreams and often find ourselves with more questions than answers. In Werner Herzong's Cave of Fogotten Dreams, Herzog is given access to a shut away world of the past. That past is in the Chauvet cave in southern France. The cave holds ancient drawings and artifacts, preserved in a pristine state. The paintings on the wall depict a time forgotten by our modern world. The drawings speak of a peoples life, world, and dreams.

Though Cave of Forgotten Dreams is a document of the discovery and scientific thoughts about the cave, it seems that Herzog's interest go beyond those modes of understanding the cave. Herzog's intentions of discovering the meaning of the images on the caves walls and their importance seems to be more of the obsession for him. Herzog's time was limited in the cave and so his crew captured as much of the accessible parts of the cave as possible. Cave of Forgotten Dreams was originally released in cinema's in a 3D. Herzog intentionally shot the interior of the cave walls in 3D so as to come as accurately as possible to sharing the symmetry of the cave walls with the rest of the world. With the release of the film on Blu-ray or DVD one could watch the film in 3D or 2D. This post about the Cave of Forgotten Dreams is written with the 2D version in mind.

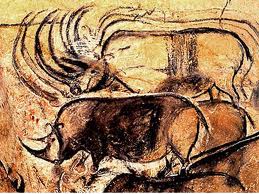

The centerpiece of Cave of Forgotten Dreams are the cave paintings. The cave paintings are mostly of animals; cave bears, horses, lions, rhinoceros and others. One part of the caves wall is covered in hand prints in red coloring. What is awe inspiring about the primitive art is the freshness of the drawings. The cave has kept near perfect drawings even after the passing of centuries. Herzog focuses on more than the drawings but rather what the artist/s has tried to depict with the drawings. The animals are not just a drawing on cave walls but there is a story that is being told. Some of the animals have more than the appropriate number of legs. Herzog describes these animals as being in motion. This motion is in a way a primitive cinematic experience. Herzog imagines the light from fires casting their flickering shadows on the walls of the cave at night. Each flicker of shadow like the passing of a film cell through a projector. When the drawings are combined with the contours of the cave walls the animals further come alive. Herzog can only speculate what the stories on these cave walls were. Even those interviewed can only see the importance of the images in an anthropological and archeological sense. But one can always imagine the stories and even the dreams of these people and Herzog tries to get us as close as possible to those dreams.

Throughout the film Herzog detaches the film from an informational documentary to a film that just captures the time and place. The cameras pan and move through the cave. The shots are sometimes wide panoramic views of the cave and then there are close-ups of the animals and the intricate design of the animals. Herzog's crew passes a light over the drawings, trying to recreate the shadows that might have existed with a fire or sunlight of century's ago. Coupled with these shots is the operatic soundtrack that adds a sense of grandeur and opus to the images. It may be a bit heavy handed but this is common Herzog device to illicit awe in the world in which he is filming. What Herzog may really be trying to do is not put music to his film but rather the story that is on the cave walls. It is as if our more modern music could capture the scope of the potential stories that the cave has to offer. In one section Herzog interviews a scientist who talks about a primitive flute that was found in a similar cave. The scientist plays the Star Spangled Banner with the flute but one can see that for a civilization years beyond our comprehension there may very well have been a full experience of sight and sound in their story telling. The primitive flute may have added a layer to the ancient story telling of the cave paintings. This further taking the cave paintings and making them extra sensory and beyond the everyday world of those people. Just as filmmakers today put us in worlds beyond ourselves with various cinematic aesthetics and technologies.

Herzog's exploration of the Chauvet cave is an exploration of the dreams of a people long gone. Their only remains can only offer us so much just as our dreams leave us with such little. Our dreams are no different from those of centuries past. Sure our tools and worlds are different, but we are still grasping at wonder and searching for the purposes of our dreams. At the end of the film Herzog tells us that the cave is being even more restricted due to the discovery of mold on the caves walls due to the explorations that have taken place. There is still much more to explore but time has a way of breaking down the dreams and desires. Langston Hughes once wrote that there are two ends to all dreams, fulfilled and unfulfilled. Both are tragedies. Such is the Cave of Forgotten Dreams.

" No other art-medium—neither painting nor poetry—can communicate the specific quality of the dream as well as the film can. When the lights go down in the cinema and this white shining point opens up for us, our gaze stops flitting hither and thither, settles and becomes quite steady. We just sit there, letting the images flow out over us. Our will ceases to function. We lose our ability to sort things out and fix them in their proper places. We're drawn into a course of events—we're participants in a dream." - Ingmar Bergman